The Phallic Fallacy

Every men’s locker room is filled with sweaty, hulking, naked guys who know exactly what women want—or do they?

Sports Illustrated Women | Spring 1997

I’m going to let you in on a secret. Call it the dirty little secret of the locker room.

The guys aren’t that attractive. Muscle definition is one thing. Going to bed with Mount Rushmore is quite another. Did somebody say rockslide?

As a sportswriter I have spent the better part of my adult life interviewing male athletes, monoliths wearing bikini briefs… or less. This unfortunate fact of life has led to an equally unfortunate and patently false assumption on the part of the subjects. They exist; therefore you want them.

As a reporter, this puts you in a compromising position, though not the one most people expect. This compromising position is no fun at all and leaves you asking yourself: What, exactly, are you supposed to do? Introduce yourself and say, “Hi, I’m Jane Leavy, and I have no desire whatsoever to sleep with you?” Experience tells me that this is not the best way to get someone to talk to you, which, after all, is part of the job. So what do you do when you cross the threshold into their stinky, sweaty, testosterone-infused lair? You hold your nose and look the other way. You don’t say the first thing that comes to mind: “Eeeew.”

I’m not alone in this. Check out the locker room scene in Jerry Maguire, the Tom Cruise ode to flexion. When a female reporter accidentally drops her microphone at the feet of an underdressed hunk, she instinctively shields her eyes. They sweat. They smell. They scratch. My fantasy, they’re not. Their fantasy is that they’re everyone’s fantasy.

I can’t say I blame them. As a culture we throw ourselves at their feet. (Some of us more literally than others.) By the time they’re 12 years old and it’s clear they can kick, pass, throw or hit the ball better than the rest of us, the seduction has begun. We woo them with freebies–sexual, legal, ethical. They romance us with prowess, feats larger than life.

After all, this is America, where bigger is presumed to be better. Big money, big cars (or smaller cars with bigger engines), big guys. We’re suckers for guys who live large. As Smokin’ Joe Frazier, the noted linguist, once told me, “Big men’s what makes the world go ’round.”

Is it any wonder they see us all as notches on their belts?

In sportswriting the deadliest of all sins is what Red Smith, the renowned sports columnist for The New York Times, called “godding up” ballplayers. Godding up means putting athletes on pedestals where they don’t belong, and in late-20th-century America, it has become both sport and industry.

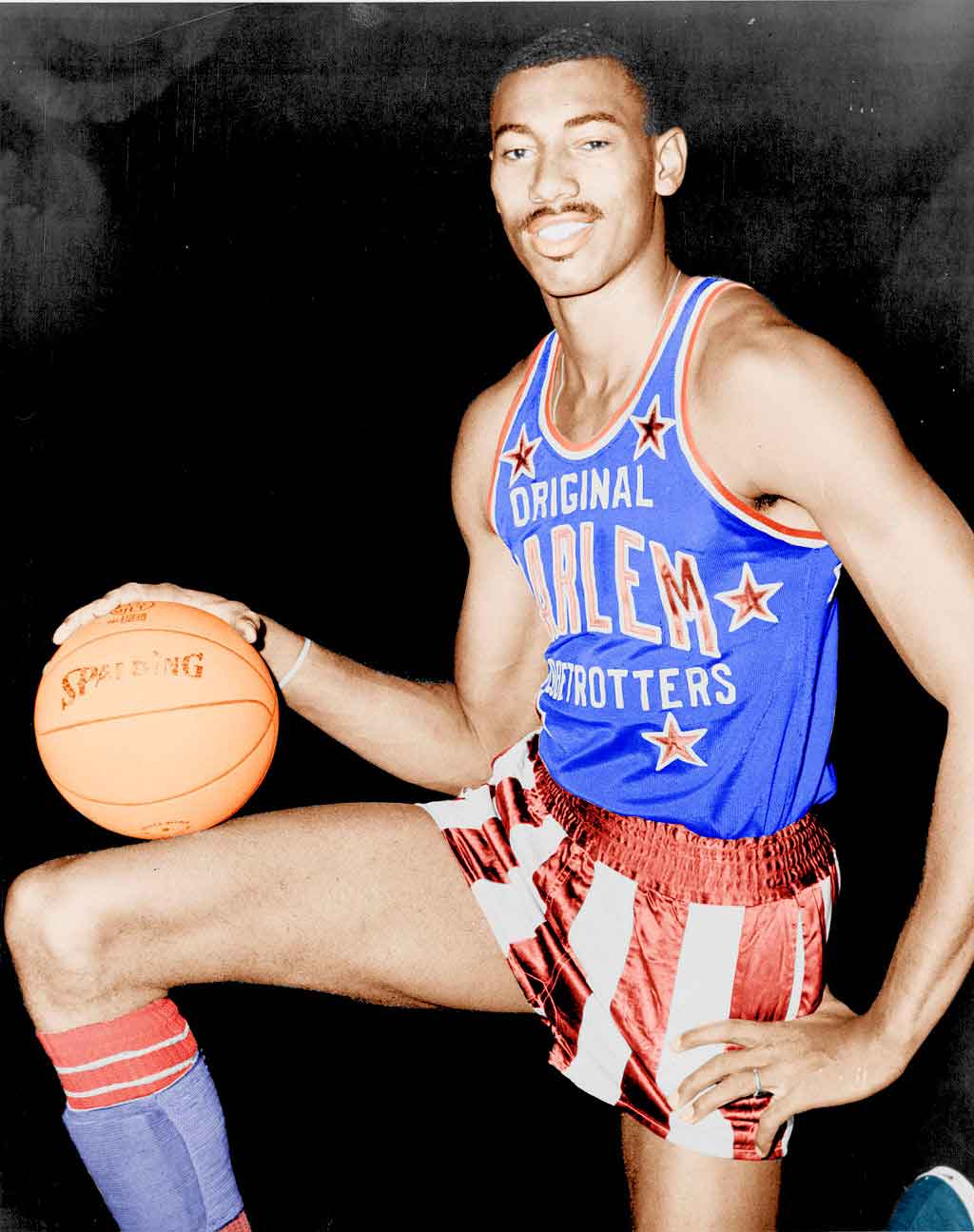

It’s no accident that Wilt Chamberlain titled his biography A View from Above. This was the literary masterpiece in which he cataloged his sexual conquests–20,000 of them. And that was six years ago.

“At my age,” Wilt wrote, “that equals out to having sex with 1.2 women a day, every day since I was fifteen years old.” I remember reading that and thinking, god, wouldn’t you just kill to be the point two? When I became a sportswriter in 1977, the unstated goal was to write lean, mean, macho prose. We couldn’t make ourselves invisible in the locker room, so we tried to make ourselves invisible in our writing.

How many times did I dare my friends to remove the byline from my stories and try to find any place where my words sounded as if they were written by a girl? We weren’t supposed to acknowledge the differences gender might produce, much less flaunt them.

But the truth is, women in the locker room do see things differently–and I don’t mean anatomically. We come to sports with different assumptions and experiences. We are outsiders, which is what reporters are supposed to be. The femininity we sought to hide is actually our greatest asset, our X-ray vision.

After all, this is America, where bigger is presumed to be better. Big money, big cars (or smaller cars with bigger engines), big guys. We’re suckers for guys who live large. As Smokin’ Joe Frazier, the noted linguist, once told me, “Big men’s what makes the world go ’round.”

Being seen isn’t the issue for athletes in the locker room. The issue is being seen for what you are. Being revealed is a whole lot more threatening than being exposed. If nakedness were really the problem, they would just put on their pants.

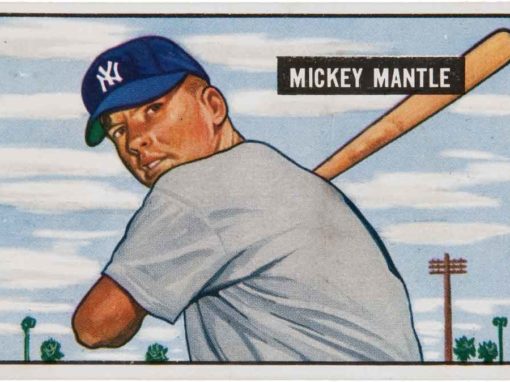

When I was a kid, my hero was Mickey Mantle. I ached for him and cheered for him not only because of what he did but also because of what he couldn’t do. I was entranced by his vulnerability, the prodigious what if that his physical limitations imposed.

By the time we met years later, he was shilling for an Atlantic City casino and I was writing about sports for The Washington Post. My childhood ended with a thud when Mickey passed out dead drunk in my lap in a poorly lit bar in the small hours of the morning.

A cocktail waitress, who had seen this act before, helped me get him to the elevator. As we waited for the car, Mickey asked me up to his room. It wasn’t a compliment being hit on by my hero. I remember thinking, He’s doing what’s expected of him. I didn’t take it personally. Nor did he when I declined the invitation.

“Oh, well,” he said. “They always called me Mighty Mouse. ‘Cause they said I was hung like him.”

It was sweet and pathetic and, of course, I never dreamed of writing it. But looking back now, I wish I had. In his own drunken and disarming way, Mickey was asking for something much more important than a quickie. He was asking to be cut down to size. He was asking to be seen as human.

More Essays