Lives to Remember: Chuck Stobbs, 1929-2008

One pitch does not make a life, even if it makes history. Chuck Stobbs knew how he would be remembered.

Washington Post | January 2, 2009

Chuck Stobbs knew how he would be remembered.

For one pitch from a lifetime of pitches, one inning of 1,900 innings, one game from 15 years in the major leagues. April 17, 1953.

It was his first start for the Nats, having been acquired in the offseason to give Washington its only left-handed pitcher. The week had been cold, wet, inhospitable for baseball. Opening Day had to be postponed. Manager Bucky Harris rearranged his pitching rotation;President Dwight D. Eisenhower rearranged his golf vacation, enabling him to return in time to throw out the first pitch.

Stobbs was a last-minute managerial decision. The Yankees had struggled a gainstanother lefty earlier that week, Harris reasoned, perhaps forgetting that Mantle had hit a game-winning grand slam off Stobbs the year before, when Stobbs was pitching for the White Sox. Stobbs held his own against the Yankees through four innings, giving up two runs, one on a wind-aided home run into the left field bleachers to diminutive Billy Martin, an omen of bigger things to come.

In the fifth inning, with New York leading 2-1, Stobbs committed pitching’s cardinal sin, walking Yogi Berra with two outs to bring Mickey Mantle to the plate. Later, as a coach with the George Washington University Colonials, Cleveland Indians, and Kansas City Royals, Stobbs always admonished young pitchers: no two-out walks.

Stobbs had been a three-letter man at Granby High School in Norfolk, where baseball was his third-best sport. As guard on Granby’s basketball team, he made the longest shot in the history of the Duke-Durham Invitational Tournament— from the opposing foul line. As quarterback, he led the Granby Comets to three undefeated seasons.He dreamed of playing in the Rose Bowl for the University ofSouthern California. But a $34,000 signing bonus from the BostonRed Sox changed his career plans and, his son said, offered an escape from an overbearing Navy father. When Stobbs made his major league debut in 1947, at age 17, he was the youngest player in the major leagues.

Now he was in his seventh season, playing with his third team. He was a control pitcher with a very good curveball and a 40-36 career record. Only 23, he had gotten old early. He didn’t throw very hard, and he hadn’t thrown much that spring because of a stiff shoulder. Harris thought he might prosper in vast Griffith Stadium, the toughest place in baseball to hit a home run.

Mantle took the first pitch for a ball. On the Yankee bench, Jim Brideweser gazed at the distant scoreboard hovering over left field and told coach Jim Turner, “I bet this kid could hit that big scoreboard.”

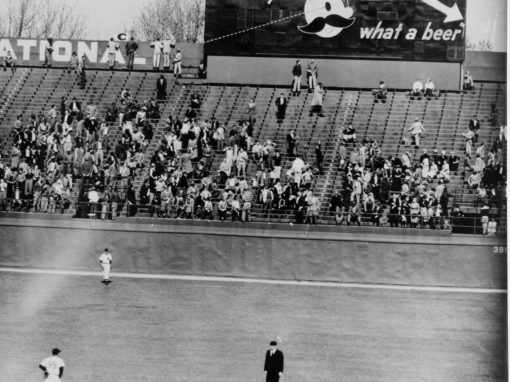

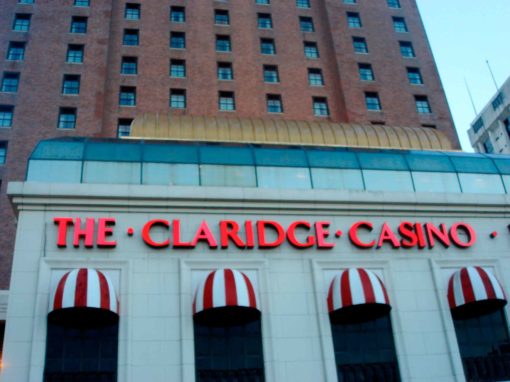

It was 391 feet to the base of the left field wall and another 69 feet to the back of the bleachers. The scoreboard projected 15 feet above the55-foot back wall of the stadium. It was adorned with the smiling visage of “Mr. Boh,” the advertising logo for NationalBohemian beer. “Naw,” Turner said, “nobody could do that.” Nobody ever had.

As Stobbs went into his windup, 11-year-old Bill Abernathy got to his feet.He and his father, two of only 4,206 paying fans, sat in the presidential box Ike had occupied the day before. “I said to myself: ‘Wow, this wind is really blowing. Straight out to left field.'”

The Weather Bureau later said gusts up to 41 mph blew toward the bleachers between 3 and 4 p.m.

The pitch was a fastball or slider. Stobbs later said he couldn’t remember which. Either way, he left it over the plate. Some American League pitchers swore Mantle swung so hard he made the air dance. He timed this swing perfectly. The ball exited the stadium so fast that Nats broadcaster Bob Wolff did not have time to raise his voice in narrative exclamation. It was hit so high, infielder Wayne Terwilliger said that “Mantle was at second base by the time it came down.” The ball kissed Mr. Boh’s cheek, knocking paint chips from his mustache as it headed toward Fifth Street NW.

“This one’s got to be measured,” Red Patterson, the Yankees public relations man declared as he dashed from the press box. He returned some innings later with a deformed ball and the astonishing and unverified news that it had traveled 565 feet, making it the longest home run ever measured. Patterson said a young boy found the ball and had taken him to its landing spot in the back yard of434 Oakdale Place.

“Mantle’s 565-Foot Homer Clears Leftfield Stands,” The Post’s headline declared. A panoramic photograph with an arrow superimposed on the stadium traced the trajectory of the ball. Thus the “tape measure home run” was born.

Patterson did not say how he measured the distance nor did any of the intrepid scribes question it. “He was the Yankee PR guy, so you accepted what he said,” Wolff said.

Mantle rounded the bases with customary modesty, head down; Stobbs lowered his head, too. “His glove fell off his hand,” Abernathy said. “He just looked at the mound.”

“Mantle’s 565-Foot Homer Clears Leftfield Stands,” The Post’s headline declared. A panoramic photograph with an arrow superimposed on the stadium traced the trajectory of the ball. Thus the “tape measure home run” was born.

Stobbs wasn’t a brooder who took the game home to his 16th Street NW apartment. But his initial good humor — “He really hit the heck out of it, didn’t he?” he told reporters after the game— was eroded when he arrived at the park one day to find a large, white painted ball on the spot where Mantle had knocked the smile off Mr. Boh’s face, not to mention his own.

On May 28, Stobbs was demoted to the bullpen, having lost five of seven starts. Three days later, the day before the bat and ball were to be sent to Cooperstown, the ball was stolen out of a display case in Yankee Stadium.

Mel Allen, the radio voice of the Yankees, took to the airwaves to appeal to the conscience of the thief. The relic was returned and sent to the Hall of Fame. The curators did not ask for the putative tape measure and for good reason. There wasn’t one, a fact Patterson did not acknowledge until the 1980s. He had paced the distance with his loafers. And, oh, by the way, he admitted cheerfully, he never said the ball traveled 565 feet in the air.

During six years with the Senators and for the rest of his baseball life, Stobbs was asked one question. “His normal answer was, ‘Thank God, it didn’t come back through the box,’ ” said his friend Bob Kleinknecht, who met Stobbs on the basketball court in the1940s.

Over time, Stobbs grew impatient with the notoriety. Why didn’t anyone point out how hard the wind was blowing? Or that the measurement was not exact? Or that in 1956, the year Mantle won the Triple Crown, he only got three hits — three singles — in 22 at bats against Chuck Stobbs?

“He hated talking about it,” said Stobbs’s grandson, Evan, a pitcher/infielder at the University of Central Florida. Stobbs helped raise Evan, taught him how to throw his palm-ball, attended his baseball games no matter how sick he was during the last seven years of his life. Evan asked his grandfather about that day only once or twice.”He said that he threw the first fastball by him, and the next pitch he threw another fastball by him, and he thought he could throw it by him again.”

Memory distorts. It distorted Stobbs’s recollection of the count—it was 1-0—just as it distorted the perception of an athletic career worthy of entry into Virginia’s Hall of Fame. Evan attended the induction ceremony in 2002. He will remember his grandfather for deeds far more substantial than a baseball that soared into myth even if no one else does.

Charles Klein Stobbs died of throat cancer at age 79 in July. He had two funerals, one in Florida, where he moved his four young children after their mother died of a brain tumor at age 40, and another in Olney, where they were married, where their children were baptized, where she was buried in 1973. No one mentioned Mickey Mantle.

A week later, Evan Stobbs got his first tattoo — a baseball adorned with his grandfather’s initials and his uniform number trailing a small spit of flame.

More Essays